For-Curators

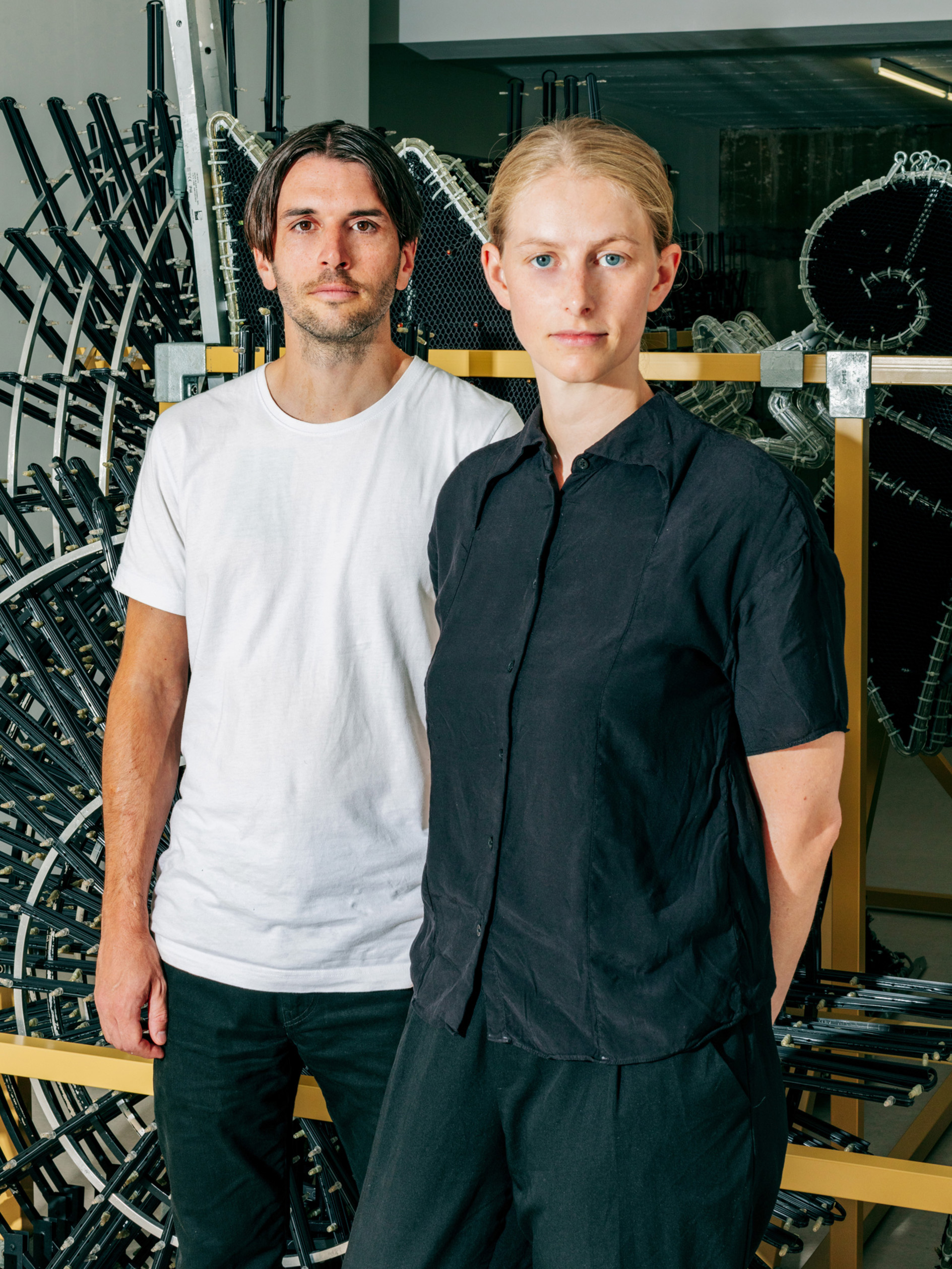

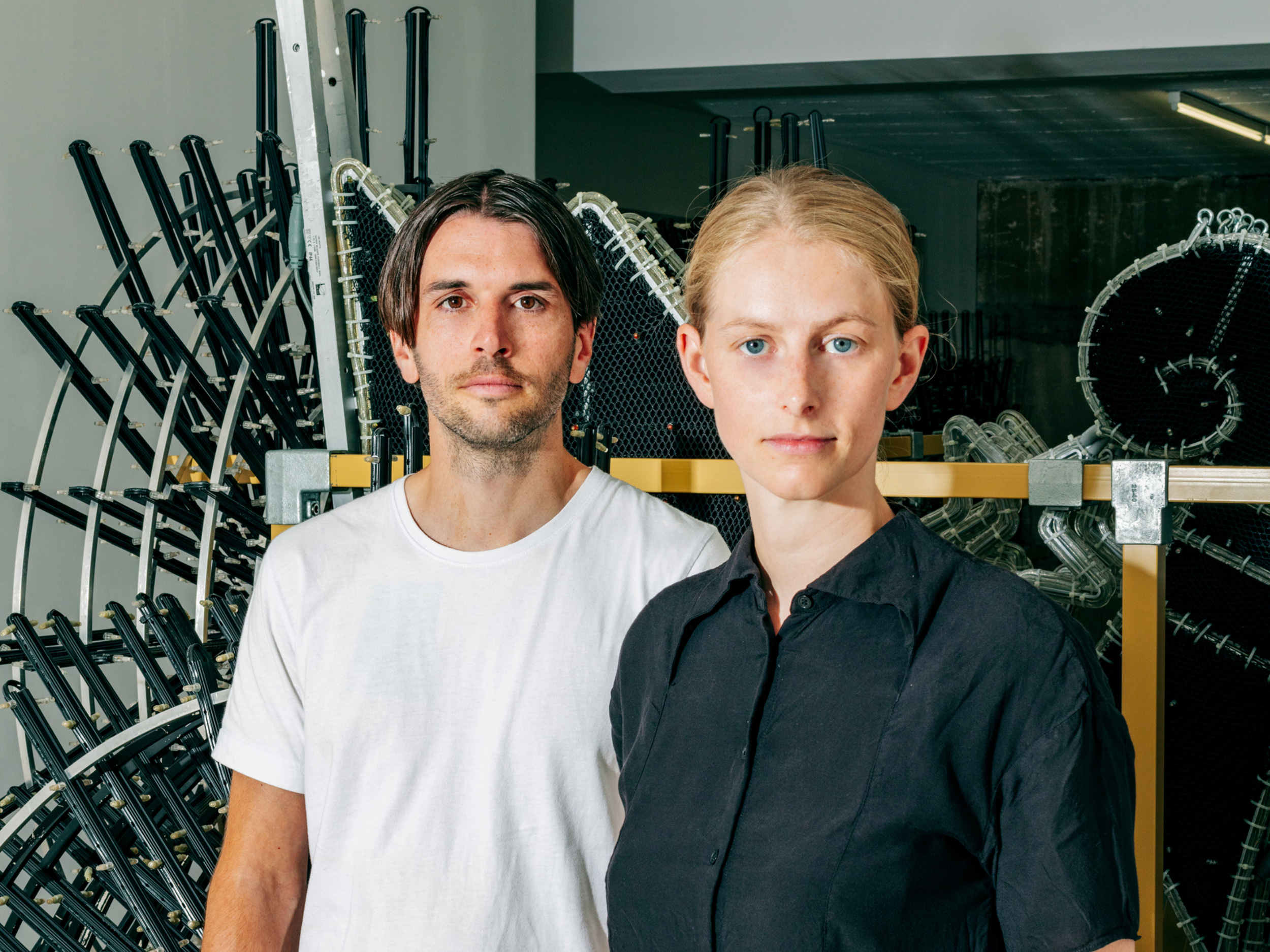

VALERIE KELLER / MATTHIAS LIECHTI

Public Christmas decorations are not really what you would expect in an exhibition of contemporary art in the middle of the summer. But then again, summer is the only time they are not needed. Judith Kakon’s exhibition entitled commuted, ordered, incited, assisted or otherwise participated would probably not be possible in the winter, at least not in its present shape and form, as seen in the rooms at For right behind Claraplatz. Born in 1988 in Basel, Kakon has opted here for a large installation for which she borrowed Christmas decorations from the producer that have already been used, as well as new ones. These decorations are all in the shape of stars or large-scale Baslerstäbe (Engl.: Basel Staffs)—the bishop’s croziers that have become a symbol of the city. For the show at For, the artist has designed a special display frame for them. They are not illuminated, and they look pretty unglamorous.

Kakon wanted to show “the Christmas decorations in the exhibition space as if in the form of storage, not lit up, as if they were asleep.” She is interested in “the relationship between emotions and capitalism.” These Christmas lights that have temporarily become art stay switched off—flying in the face of convention—and encouraging us to reflect on capitalism and its mechanisms. Why is the imperative to consume at its strongest at Christmas, the “season of love”? What do love and consumption have to do with one another? “Emotional capitalism,” the subject of the work of French Israeli sociologist Eva Illouz, is a complicated matter, and her ideas form the theoretical backdrop to Kakon’s impressive installation of borrowed objects.

“We have learned to communicate our love to our loved ones through commodities,” write the For directors Valerie Keller and Matthias Liechti in their editorial in the publication accompanying Kakon’s exhibition, which will be released during Kunsttage Basel. But it doesn’t have to stay this way. “The will to understand the glowing stars in this way is waning, and the time seems ready for a collective reinterpretation”. This critical, analytical, non-affirmative view of the present day is typical of the approach taken to curating and publishing at For. Kakon’s show is the third exhibition in this relatively young off-space, which first opened in autumn of 2022. The plan is to present four exhibitions and publish four magazines per year or season. The program focuses on modern media, popular culture, the economy, the city, and all the various relationships that shape today’s society, reflected through the mirror of contemporary art.

Keller and Liechti are both originally from Bern. They gained experience there between 2015 and 2020 as co-operators of the non-commercial exhibition venue Milieu. For For, they have developed a programmatic and prolific connection between cultural theory and contemporary artistic practice. Born in 1989, Keller has a doctorate in cultural studies and works as a lecturer with a postdoctoral position at the Department of Social Anthropology and Cultural Studies (ISEK) at the University of Zurich. Liechti, who was also born in 1988, studied in Bern and Zurich and is a practicing artist—his work comprises drawings and the production of objects and installations. Keller and Liechti like the fact that Basel has “an audience that is very interested in culture,” that the various scenes are interconnected, and that there is a lively interest in discussion and debate in the city.

Their website describes For as a “not-for-profit exhibition space.” The architecture of the building combines the raw and brutalist look of shell construction with elements of the white cube. This confluence of diverging codes and atmospheres is intentional. Keller and Liechti are interested in critiquing the conventions of displaying art.

“We wanted a ‘white cube’ that would reveal its own modus operandi.”

The two exhibition makers are just as interested in how things are shown as in what is shown. They ask pretty much all the basic questions: How do we talk about art? How is art disseminated? How do we ourselves wish to talk about art? This ambitious approach is also reflected in their publications—every exhibition is accompanied by a printed publication in an edition of one hundred. The pdf is made available on the website too. The format is that of a magazine with a single theme explored in three or four associative essays. There is no attempt to “explain” what is shown in the exhibitions. “Each issue has the character of a collection of reflections and perspectives that have some connection to the exhibition in question,” explain Keller and Liechti. Each publication also invites the audience to engage with the exhibition after their visit and further explore its themes. So far, these magazines have addressed – among other topics – the potential of melancholy, discussed the contradictory connections between revenue from property and the patronage of the art scene, and asked why it is worth re-reading Astrid Lindgren’s classic children’s book Pippi Longstocking.

Keller and Liechti are already working on their next exhibition with the Egyptian artist Yasmine El Meleegy. The opening of her solo show at For, entitled The six hundred seventy-four forms and a dragon, is scheduled for the end of September 2023. Meleegy describes herself as a multidisciplinary artist, sculptress, researcher, and “archeologist traveling in time.” Her research project Future Farms, which she has been working on since 2013, will feature in the exhibition, while surprises are to be expected. A white cube that lays bare its own ways of operating can also be many other things: an excavation site, a search engine, and a time machine all rolled into one.

Text: Kito Nedo

Photos: Pati Grabowicz

Transdisciplinary Artist

THY TRUONG

Thy Truong’s (she/they) main occupation is creating sound-space landscapes from memories. Truong is a transdisciplinary art and cultural producer. In addition to sound experiences, Truong also works with “sculptural objects,” as Truong calls them. “The concept of ‘sculpture’ is too static to describe what I do. My works are in constant movement. I like to use fleeting ‘thin’ materials such as thickened acrylic drawings that rotate and thus keep disappearing into space,” Truong explains. The work takes place initially in phases devoted to the necessary mental recuperation within the spectrum in which Truong operates: “It might be the case that I write down fragmented ideas over several weeks, often in the train or somewhere in the countryside. Mostly, these ideas then enter into my work in poetic form. Then, other elements are added: drawings, research, and experiments with objects, sounds, noises, and music. It is very important to consider how the viewers may experience my words.”

The themes of Truong’s works are personal memories and growing up in bicultural contexts. For Truong, exploring these topics holds a special quality: “These are themes that do not always have a place in our everyday lives but are very important for individual people. I was five years old when I left Vietnam for Switzerland. This was a formative time for me and left me with a multitude of impressions—they are a part of me, of my history, my biography, and my identity. They contribute to who I am today. This process of recollecting navigates the direction I’m steering towards.” Truong wants to add new, positive facets to the public discourse on themes like migration and the development of identity between different cultures and thus counter-trends that problematize this. Truong is certain that everyone can take something of their own from ideas like collective remembering:

“Ultimately, everyone is made of memories. This is the only thing that remains of us when we go.”

Regarding the musical aspects of their work, Truong came to music and sound via a series of coincidences—thankfully. In the final year as a fine art student, studio partner Jasper Mehler asked if Truong might like to try DJ-ing. Truong spontaneously answered that it would have to be the annual Christmas party of the Institute Art Gender Nature at HGK. What started out as a joke led to a first gig. Truong remembers: “At first, I was reluctant to the idea of standing behind a DJ’s deck, even though I was fascinated by club music: the entertainment element was too strong for me, with the DJ standing like a ‘god’ at the center of attention. Then I realized that all the stereotypes just distracted from what really matters. Today, the most important thing for me is to tell stories.” The newbie DJ, soon became a hot act—thanks to friends who were already well-networked and active in the scene. Truong played at last year’s Art Basel at the Tristesse party, which always pokes a bit of fun at the exclusivity of the art market. The success of Truong’s sets is due to the friction they create between alternating soft and rough tones, done subtly and without going too far, because “sound can sometimes set off ‘triggering’ memories.” At some point, it was not enough in musical terms to combine other people’s sounds, so Truong began to produce work to complement their artistic practice, which today is a meld of sounds, texts, and objects. An aspect that Truong particularly likes: “While DJ-ing is always very spontaneous no matter how much you prepare, and it permits a certain freedom to take in the energies around you, my own creations are mostly inseparable from the installations they are part of.”

After nearly three years of intensive work and various other projects (including at Sondershop and limb limb limb with performance artist Tyra Wigg), Truong will begin their master’s studies this fall. As part of this, they would like, at the same time, to further explore variants of sound and of listening. Given the fruits of the first “experiments,” we can be excited about what comes next and look forward to whatever many-faceted creations Truong conjures up.

Truong can be seen behind the turntables during the Kunsttage Basel Night on Saturday, August 26, 2023, from 7 pm in the K-Haus for those who don’t want to wait for the next audiovisual projects.

Text: Samara Leite Walt

Photos: Jana Jenarin Beyerlein

Artist

ERIC HATTAN

Off-spaces, those non-commercial art venues that are neither galleries nor museums, usually have relatively short life spans. After around two years, the moment comes to ask what the next steps should be: dissolution, professionalization, moving to a new location, or reorientation? That’s the way it goes. But there are exceptions. Some of these spaces and initiatives manage to keep on reinventing themselves for many years or even decades. Filiale is a case in point—an independent project space first founded in 1981 and still going strong today. After a number of closures, interludes, and reopenings in different parts of the city, this summer, once again, there will be exhibitions presented under the name of the Filiale—this time in a former bike shop in the Kleinbasel district at the corner of Hammerstrasse and Sperrstrasse that has been converted into a temporary exhibition space.

Nightprayers is the current show’s title with works by painter, photographer, and object artist Rut Himmelsbach, with her special guest Jacob Ott. Himmelsbach has made an arrangement of around three dozen stones and other objects in a glass cabinet. She gathered these stones on the shore of Lake Atitlán in Guatemala. Their random shapes resemble—some more so and some less—the heads of small dogs. These allusions are complemented by the sound of dogs barking at night, emanating from a loudspeaker concealed in a metal tub, and a painting of the moon on the adjacent wall. Ott has also added three designs for plinths inspired by architectural models. During Kunsttage Basel, two further exhibitions will be presented just around the corner in Eric Hattan’s studio. Bildhauer: Stäuble, Voita, Hattan, Leiß presents four artists, each showing one sculpture and one photograph. In the large installation Ordnung schaffen, artist Claude Gaçon presents his collection of round objects and artifacts.

“I no longer have anything to prove,” Hattan says—he has kept Filiale going for more than thirty years now, doing it “just for the fun of it.” This sounds rather laid-back. But even at the age of sixty-eight, Hattan is passionate about art. You notice that right away. The artist and project maker was born in 1955 in the Swiss canton of Aargau. In 1977, in his early twenties, he moved to Basel to begin training as an art teacher at Kunstgewerbeschule (Engl.: the school of arts and crafts), but he dropped out shortly after. Instead of teaching art, he became an artist.

“When we first opened the Filiale in 1981, this city was very different,”

Hattan says, looking back at the early days. “There was very little or perhaps even no opportunity for young artists to show their works.” The scene then organized and created its own spaces. Hattan and his partners at the time, Silvia Bächli, Heide Hölscher, and Beat Wismer, were not only interested in showing self-organized exhibitions but also wanted to establish a space that would be open all year round, a place for artists in Basel and environs to meet and network with one another. The tiny budgets for exhibitions were partly financed by the sales of art editions.

Hattan taught himself how the business of art and exhibitions operates. It was learning by doing. At the time, Kunsthalle Basel also offered a form of “education”—Jean-Christophe Ammann was the director and organizer of the program of exhibitions from 1978 to 1988. Hattan says that in those years, he was often asked what he really was—an artist, a gallery owner, or a curator? As if it was essential to settle on a particular function or role. He saw himself as an intermediary, a “disseminator of art, information, and spaces.” This was certainly his approach in 1987, when he initiated and organized the temporary conversion of an old factory building as the “Stücki-Areal” with studios for around two dozen artists. The artist is concerned with “spaces” both in the context of his own artwork and also in his practice as an art activist. “It is never just about art. I am operating in a field with architecture and social behavior,” Hattan explains. “I am interested in spaces—as abstract entities and in terms of what happens in them.”

As a citizen of Basel, Hattan has not been shy of voicing criticism in public. In 2019, he held a much-discussed speech at the ceremony at Kunstmuseum Basel marking “100 Years of the Basel Kunstkredit,” in which he took issue with the Kunsthalle Basel’s exhibition program: “From the Kunsthalle, I expect more commitment to art from Basel, more than just giving the Kunstkredit a space as a guest.” But now Hattan no longer wishes to make appearances in public. “I think it is time for younger people to take over the role of critic,” he explains. But delegating this task to others will certainly not be the end of his critical and productive participation in the city’s art scene, now in post-pandemic times.

Text: Kito Nedo

Photos: Pati Grabowicz

Curators

LUST*ART

“It would have been easy to applaud the artworks exhibited as a new critical departure from the—almost—too conventional way of seeing queer art. Yet, the greatness of this exhibition lies in the actual absence of greatness. This does not claim that these works are not excellent nor that nothing or nobody is truly special, but rather we understand that all moments, all experiences, all types of joy, and disappointments are equally relevant or even equally insignificant.”

This is the answer given by the makers of Lust*Art when asked to describe themselves in a nutshell. When we sat down with them to chat, they were right in the middle of planning the next three-day happening at Kasko project space. That they have much more to say is proven by this interview with Bebbi Zine editor Samara Leite Walt, who talked to the team of three curators: Maria Fratta and Pietro Vitali, who put together the program for the past edition, and the new addition Stella Auburger, who alongside her work for Lust*Art also works as a graphic designer for the Luststreifen Film Festival Basel, the queer-feminist sibling founded in 2007 that led to the current project.

Leite Walt: First things first: Who are you and how did you get involved in Lust*Art?

Fratta: We are three friends who met each other when studying for the master’s in Visual Communication and Iconic Research at HGK. Pietro and I have roots in Italy, and Stella originally comes from Germany. Funnily enough, we were all three newcomers to Basel who arrived during the pandemic, looking for projects that would inspire us and also enable us to link up with the queer and cultural scenes here. Our paths to Luststreifen Film Festival Basel and then to Lust*Art were all different and all very organic. We began as visitors at first, before deciding at different times to become team members.

Vitali: What we liked most was the accessibility of the Basel scene and the safe spaces that the festival and its program of events offer. Before then, we were looking for places where we could operate in this city, which was new for us at the time. Thanks to this welcoming community, we realized at a certain point that we would like to help shape the scene.

Leite Walt: To what extent does this support of the local (queer-feminist) scene play a role in the organization of Lust*Art?

Fratta: We have a lot to thank the Luststreifen family for. After Lust*Art first took place within the festival program, and then was later moved to Kunsttage Basel, all the contacts and relationships that we had gotten from our festival buddies were worth their weight in gold!

Vitali: The support from other creators of art and culture was really important for location scouting too. Contacts from the Wildwuchs festival, for example, helped us to approach Kasko, where this year’s edition is being held alongside their offices. Their team has given us free rein and is supporting us with art educators to ensure that all the visitors can experience inspiring and stimulating visits.

Leite Walt: In your program text, you say that you want to create a safe space “where lust, dreams, different forms of love, fluidity, intersectionality, and sex and body positivity can all come to life.” How are you doing this?

Vitali: Lust*Art has separated from the official film festival regarding timing and scheduling, but the values remain the same. We want to expand our audience, beginning with this “bubble.” We want to plant our ideas into other contexts and thus sensitize others to queer issues, making them real and tangible for them. This often takes place through our selection of people to work with and of artists to participate in the exhibition. We still wish to position ourselves as a queer art space. There are some safe spaces, of course, but hardly any spaces in the art world that so clearly say that of themselves.

Leite Walt: So, what is queer art for you?

Auburger: We don’t want to claim to define the levels of queerness of the artists or their works. Our focus is always on the critical space in which queer sensibilities are located and made visible. As curators, we do, of course, come up against certain defining limits. But we are interested precisely in this vulnerability of queer art, which we see as an independent quality of this art.

We do not define queerness; we appreciate its diversity.

Vitali: Of course, the positions must somehow be located within the broader queer-feminist context, and the works must personally resonate with us and contribute to the platform as a whole. We also take the time to meet the artists personally and to exchange views with them. It is important not just to show art but to work on it together with others, to help them express their artistic visions in ways that we all feel comfortable with, so that it all feels right for us and everyone participating.

Fratta: We are trying to humanize the experience of exhibitions, which can often otherwise quickly feel very “sterile.”

Leite Walt: One last question: Can you give some details of the program that people can look forward to this year?

Auburger: The program is not yet official, but we want to cover a large spectrum of different artistic disciplines. From performances, installations, photography, sculpture, and painting, all the way to short films—all of these will be included. Among the artworks and performances, there are lots to look forward to. Still, we are particularly excited about works by Du Yan from Zurich and the Screens*Scream*Sex collective, because they stand for the phenomenally broad range we have and perfectly fit our curatorial principles.

Vitali: We are also working on founding a permanent Lust*Art location. This would mean that our ideas can resonate for longer than three days and that more people can come along and realize their projects at our venue.

Auburger: Ultimately, the entire Lust*Art project lives from all the people contributing to it.

Text: Samara Leite Walt

Photos: Jana Jenarin Beyerlein

Artist

ANNETTE BARCELO

Annette Barcelo prefers to work directly on the canvas or paper, forgoing any initial studies or sketches.

“I’m impatient,”

she says. Recent drawings hang on the wall of her studio: fantastical beings drawn with charcoal on paper. In some places, one can see how the artist has worked directly with her hands. Barcelo has added wild manes and hairstyles to her creatures. Hollow eye sockets in pitch black abound. There is something ghostly about them. As if they inhabit a liminal zone—a twilight world or shadow realm. On another studio wall hang small, intensely colored paintings behind glass. Their subject matter conjures up surrealist scenes. But Barcelo rejects such labeling. “The surreal is not desired,” she says. The artist prefers to speak of “soul animals” or “soul family.” Barcelo is passionate about medieval art. And in particular the work of Giotto di Bondone—or Giotto, as he is known—because of his use of color and dense visual language.

Live Your Transformation is the title of the exhibition of Barcelo’s work that will be shown during art fair week in der TANK, the exhibition space of the Institute Art Gender Nature (IAGN) at the Basel Academy of Art and Design FHNW. The artist was invited by the internationally renowned curator and head of IAGN, Chus Martínez. The timing is perfect: the show coincides with Barcelo’s eightieth birthday.

“Basel is my place—this is where my roots are,” says the artist, who was born in 1943. She is not “fixated on Basel.” In her youth, she attended a preliminary course at Kunstgewerbeschule, the school of arts and crafts, but she was also interested in dance, ballet, and gymnastics. She married young and raised four children. One of her sons, architect Jordi Barcelo, played a leading role—together with his wife, Katrin Baumann—in the design and realization of the new studio building at Wiesenplatz in Kleinhüningen, built in 2009 by ARGE Barcelo Baumann Architects and Kräuchi Architects ETH SIA. Barcelo has a studio in the building.

Her art is not limited to studio production. Barcelo lives with graphic artist Thomas Dettwiler who, until 2017, taught hand-printing techniques at the Schule für Gestaltung. The artist pulls out a self-bound book titled Engel [Angels] with twelve drypoint engravings. The book was published by Dettwiler’s Hohe Winde Presse, which specializes in print editions of graphic works. “Instead of a living room, we have a printing studio and two printing presses at home,” Barcelo adds, smiling at the sheer ubiquity of artistic means of production surrounding her.

Text: Kito Nedo

Photos: Pati Grabowicz

Technologist

Ronja Kübler

How is art created? The conventional answer is that it is created in the eye of the observer through the act of observation. But this tells us nothing about the process of its production, which happens in places like the massive workshop in Münchenstein’s industrial zone. For what is concealed behind door no. 10 bearing the sign “Kunstbetrieb” actually feels like a revelation.

A few years back, for example, a statue of liberty was produced in the workshop behind this factory door. Not the one by Frédéric-Auguste Bartholdi that has towered above the New York skyline on Liberty Island since 1886, but a life-size replica of it. Consisting of approximately 250 sections of copper sheeting, it bears the title We the People, which are the oft-cited first words of the US Constitution. The author of this piece of sculptural conceptual art is the Danish Vietnamese artist Danh Vo. It is truly a mind-boggling undertaking. And this is precisely why artists such as Urs Fischer, Sylvie Fleury, Pamela Rosenkranz, Andro Wekua, Franz West, and Pedro Wirz came to the art foundry with their ideas, taking advantage of the skill and expertise available.

Ronja Kübler has also been learning this specialist knowledge for nearly two years now, as part of her training to become a casting technologist for lost forms. It was while studying fine art at the Basel Academy of Art and Design FHNW that she realized just how much she was fascinated by materials and the study of forms. This underscored her decision to train in a program that focused on metal as a material.

Raphaël Schmid, the art foundry master, who serves as Kübler’s main point of contact during her training, waves us over. Kübler puts on protective clothing and then embarks on the aluminum cast. At the same time, four people are busy pouring the red-hot mass into the prepared chamotte cubes. The concentration and tension are palpable. After a few moments, the well-practiced maneuver is completed. Now it’s all about waiting. “It takes about three hours,” explains Kübler, at which point the cast segments will have cooled down enough to be unpacked. That moment, when the cast body is unpacked, when negative becomes positive again, is one of the most beautiful moments, period. Is that when art is created? Kübler has to think about that: “No, the work of art exists before it comes to us, as an idea.” In this case, it is the artist Maitha Abdalla who is having her sculptures cast and patinated for the exhibition

Evaporating Suns: Contemporary Myths from the Arabian Gulf at Kulturstiftung Basel H. Geiger. In general, Kübler seems to have a surprisingly pragmatic attitude toward the artworks and the art market. What interests her is the technical aspect of it all: amassing more knowledge so that she can help others produce their art in the future.

Text: Claudio Vogt

Photos: Jana Jenarin Beyerlein

Artist

GINA FOLLY

Gina Folly is always moving, and when she speaks, the words just seem to gush out of her. After her vocational training in photography, she embarked on an art degree at Zurich University of the Arts. “For a long time I saw myself in a dual role. On the one hand as an artist, and, on the other, as a photographer.” She more or less managed to keep these two activities separate for her exhibition projects and residencies in New York, Paris, Rome, Vienna, and Zurich—until now, that is, with the project on her own home turf, her Autofokus exhibition at Kunstmuseum Basel | Gegenwart, which marks her winning of the 2023 Manor Art Prize.

For this project, Folly, who was born in Zurich in 1983 and is now a resident of Basel, returned to Thalwil, where she grew up, and took photos of Quasitutto, an association of retirees who, as their website states, “supply, maintain, and dispose of” just about everything. They sew curtains, clear out apartments, do garden work, and repair household appliances. Folly photographed the retirees as they carried out their tasks. Her images are touching portraits of everyday life, and yet they seem as if they are from another time. This might be due to the dated clothing or the old furniture in them, but it may also be down to the look of Folly’s analog photographs. One constant, however, is the feeling that courses through everyone who looks at these images. And this is where the photographer comes full circle. During our meeting, Folly spoke—just as her subjects do—of the “need to be needed.”

The cycle of life is a common theme weaving its way through Folly’s work. A trip to Japan awakened the photographer’s interest in botany. In 2013, she staged an art installation with bamboo, ginger, succulents, and other young plants. A later installation, Youth (2015), was a replica of the type of perpetual water fountain used by street vendors in Rome to keep their exotic fruits cool. This was followed in 2021 by a series of photograms displaying sayings such as No Time to Die, made using the bones of dead animals that she collected on the Frioul Islands off the coast of Marseille. More lively, and therefore perhaps more touching, is her latest series of works, which is on display in the current exhibition. Folly’s photographic eye focuses on the life phase that comes after work—a time that is becoming increasingly important for our aging societies. In doing so, she forms a pact with the people she photographs and gets in line with them. Folly takes a personal approach in which she draws upon her calling and a métier that she has never really felt able to include in her artistic work until now: photography. She even takes things one step further by employing a medium that has been overtaken by the fast-moving times and is now in decline. As Folly puts it,

“Analog photography is like the retiree of the photography world.”

Sculpture has a role to play in the exhibition, too. Folly installed labeled benches, which serve as a placeholder of sorts for outmoded brands such as Agfa, Kodak, or Fujifilm. The retirees’ tired old bones will certainly thank her for them. But Folly herself isn’t ready to take a break: she’s sure to be getting started with—or to have already embarked upon—her next project.

Text: Claudio Vogt

Photos: Jana Jenarin Beyerlein

Research-Collective

HYBRID PROJECT SPACE

No sooner had this collective been launched—with its “open research” weekend at kHaus in March—than it left its first major mark on Basel’s cultural scene: the Hybrid Project Space collective. The panel discussion on diversity and accessibility in art and cultural spaces featured illustrious speakers including Kabelo Malatsie, the new director of Kunsthalle Bern; artist Va-Bene Elikem Fiatsi; and Matylda Krzykowski, artistic director of CIVIC. The newly founded group believes in dialogue, interaction, and the right to be heard—not only for institutions and their actors but also for their audience and throughout society. Their mission? To question the existing structures and practices of Swiss art and cultural institutions and to stimulate debate. The goal is to establish inclusive cultural centers where everyone can feel welcome. The group came together in their shared frustration about the lack of diversity in the committees shaping cultural policies, in the selection of artists for exhibitions, and in the failure of the institutions to reach their audience.

The collective is very clear about its own role in the process: “We regard ourselves as facilitators,” says architect Edward Wang.

“We’re happy when we succeed in allowing others to shine by creating space for them, when we see them thrive in their particular field of activity.” His partner in the collective, visual artist Gourav Neogi, adds: “We want the collective to distinguish itself by its shared mission; we don’t want to put ourselves in the forefront as individuals.” They are also reluctant to squeeze their research into a methodological corset. To them, the term “research” is more of an ongoing appeal to train attention on areas that privileged actors tend to turn a blind eye to, and to focus on awkward questions that the recipients have long been pondering. “We’re tired of top-down discourse; we want to break through this form of agenda setting. We want to begin at the bottom, with their own defined target group and one that has hitherto been disregarded—to hear their voices and make them audible and tangible for a wider audience,” says Ananda Schmidt, one of the two initiators of the project. Here, Neogi adds: “We try to avoid this linear treatment with seemingly quick and easy solutions. The issue itself is too complex for us to seek or be eager to present fast, simple conclusions. At the moment, we’re focusing mainly on posing interactive questions. The very way in which we ask our questions has an impact on the discourse. So, when we ask, ‘What makes art and cultural spaces inaccessible and non-diverse?,’ it’s already a methodology in itself.”

In this process, they continually interrogate themselves and their approach. Although parts of the group themselves work in prestigious institutions, they do not hesitate to question the institution’s intentions behind a potential collaboration. Nahom Mehret, a business psychologist in the making, comments: “Since the event at kHaus, we’ve been getting a good number of inquiries from institutions. But we shouldn’t forget what originally brought us together. That’s an area where we refuse to compromise. So we double-check every inquiry before we agree to anything. We don’t want to end up being nothing but ‘token diversity figures’ for third parties. If the inquirer’s intentions are genuine, we’re happy to accompany them on their path to inclusivity.”

To make sure they don’t forget their mission, the spaces in the Wettsteinquartier that they share with Symbiont are full of memos containing their core questions. Written on colorful Post-its or white paper, they festoon the entire room. But when asked about their definition of inclusion, their answers are as multifaceted as the theme of intersectionality. For example, graphic artist Semaya Mehret says: “To feel represented. When I was younger, I didn’t have that feeling very often. And that made me start to doubt my own worth. Then, when I started seeing people who looked like me and whose works were being shown in museums or who held management positions, my confidence increased. It’s true what they say:

‘Representation matters!’”

Co-initiator Laura Schläpfer feels that the concept is hard to pin down: “Semaya’s remarks are part of a larger mosaic. I think it’s intriguing to regard inclusion as a complex construct while also allowing different perspectives on it. For me, this is one of the keys to mutual understanding.” The group smiles and nods, and as the interviewer, one knows that when it comes to Basel’s future players in cultural politics, nobody needs to worry about the next generation.

Text: Samara Leite Walt

Photos: Jana Jenarin Beyerlein

Author

ARIANE KOCH

Ariane Koch is ubiquitous. After studying fine arts and interdisciplinarity in Basel and Bern, she began writing. Since 2013, she has produced a wide range of work, from theater and performance texts to radio plays and prose, often in collaboration with the theater group GKW (Moïra Gilliéron, Ariane Koch, and Zino Wey) or artist Sarina Scheidegger. Her texts are highly precise, frequently veering off into the absurd, yet never entirely losing themselves. This also applies to her first novel Die Aufdrängung [The Imposition], published by Suhrkamp Verlag in 2021 and awarded the Aspekte Literature Prize, which is sponsored by the German television channel ZDF. Since 2019, Koch has taught at the Basel Academy of Art and Design FHNW, this year becoming in-house playwright at Theater Basel. How does she do it?

This interview purposely avoids answering this frequently asked question. Perhaps because neither the question nor the standard answers to it are particularly interesting, at least not to Koch, who finds formal requirements tedious. “Come on,” she says at the beginning of her conversation with Naomi Gregoris, “let’s drop the journalistic obsession with authors, and just forget the questions—all except one, which you can answer for me.”

Ariane Koch: Naomi, what will my next novel be about?

Naomi Gregoris: I read somewhere that it tells the story of a geological fault researcher. For me, that conjures up associations with a glacial crevasse. The word has an archaic, primeval ring to it, something I don’t affiliate with today’s world. For me, research is something antiquated.

AK: Do you have the feeling scientific work has fallen into disrepute?

NG: The image of someone “dangling in a cold glacial crevasse exposed to the elements” makes me think not so much of scholarship as of exploration and discovery. But, of course, that image has decidedly romantic overtones.

AK: I find human beings have an urge to mystify things, now that practically everything has been discovered and illuminated.

NG: Do you mean by actually finding something new or just by romanticizing things that we already know about?

AK: Perhaps I mean something more akin to adopting a new perspective. I recently had a discussion with the author Friederike Kretzen, who told me she had noticed that artists have a tendency either to refuse to draw on historical objects and forms in their work or to turn a blind eye to them. I found that interesting: Why deny that we already have a basis for creating something new? Take the climate crisis, for example, where it certainly makes sense to draw on existing knowledge.

NG: Perhaps it’s simply a reaction to a feeling of powerlessness. One has nothing to lose, so instead one decides to leap into the void, so to speak.

AK: Instead of remaining confined by a backward-looking stance.

NG: We are also very much connected with the future. But actually what you say reminds me of the big tech companies, who always employ a philosopher so they have at least one person thinking outside the box.

AK: I was once invited to a think tank, where I was supposed to discuss future scenarios with a physicist philosopher and an IT person. I found the two of them very interesting, but I also sensed an expectation that I was there to supply the artist’s point of view.Isn’t it difficult as an artist to reconcile the outside world’s rigidly defined expectations with your own work, which doesn’t fit into this kind of predefined format?

AK: What I hate most is having to explain my work.

NG: Yes, because something always gets lost in the process. And people demand something from you that is not part of your work as an artist.

AK: That’s why I prefer to respond to art with artistic forms, so that there is at least some attempt to retain an aesthetic mode of thinking in the reception of a work of art.

NG: I think that’s why traditional cultural journalism goes against the grain for me. I simply find this constant repetition of the same old questions and the same old formats dull.

AK: Perhaps artists ought to write reviews of their work themselves. Either way, we have to do the communication.

NG: Do you like that kind of work?

AK: Well, it’s awfully repetitive. When I do readings, I notice myself becoming increasingly dissatisfied because I seem to always be saying the same thing over and over, even if the texts themselves change over time in response to the world around me.

NG: Do you feel somehow obligated to the audience?

AK: What bugs me more is that I get bored with myself, that I can no longer surprise myself.

NG: Are you able to do so otherwise?

AK: Yes, if I manage to break out of the traditional mold of conveying information. I have recently started doing readings together with a musician, for example. There, I’m surprised to find I have the courage to sing. But what does the audience get out of it?

NG: That’s great that you don’t anticipate the reaction and confine yourself to it but instead do what feels right for you. And that’s actually also a kind of exploration—not giving in to this feeling of obligation toward the audience.

AK: Yes, exploring the unexpected.

NG: Which brings us back to the crevasse researcher.

Text: Naomi Gregoris

Photos: Pati Grabowicz

Gastronomy-Project

CANAPÉ

Like every good gastronomy story, the one of the nomadic Canapé bar began with a bottle of wine. Zarina Friedli was sitting with her former roommate Luzius Bauer at the kitchen table in their shared apartment in Rheingasse and discussing their beautiful atrium. Friedli knew right away that they should do something with it: “Preferably something near the windowsills, so that people can sit and have something to eat with a view of the courtyard.”

Although they first dismissed it as a wild idea, the project soon began to take shape. “Luzius often has to suffer through my crazy schemes,” Friedl explains, “but he usually ends up on board.” They were soon joined by Johannes Heydrich and Sabeth Weibel. What do the four of them have in common? They’re all around the age of thirty, and they all live—or have lived—in the same residential project in Kleinbasel. When they’re not making canapés, the group’s members are active in the scenography, music, and fashion scenes. Working together with interaction designer Lea Ermuth, who supplied the visuals for the first manifestation of Canapé, the team opened shop in fall 2021. Why open-faced sandwiches? “We wanted to offer something simple and easy,” Friedli explains. “Open-faced sandwiches are an underappreciated delicacy.” They are served casually in the living area, which was lovingly done up before opening. Enthusiasm for this innovative dining format quickly spread among their larger circle of friends, and it became increasingly difficult for people to get a table. The sandwich bar has returned for this year’s Art Basel after temporarily setting up shop at the offices of Bajour and in Wettstein Park on the Rhine. The group continues to stick with their nomadic concept and is now supported by two additional team members: cook Roman Menge from bar/restaurant Werk 8 and architect Béla Dalcher. Canapé has once again found an exceptional setting and venue for the 2023 pop-up season: an empty garage near Kaserne Basel performance center. The menu is aimed at both longtime Basel residents as well as adventurous visitors. Friedli sums up the Canapé team’s shared philosophy:

“The most important thing is for us and our guests to have fun and that everyone feels welcome.”

“This is something we also want to reflect in our prices. That’s why we offer quality sandwiches and exquisite natural wines at affordable prices. We believe it is particularly important to offer an alternative to the high prices that are common during Art Basel.” In addition to culinary art, this year’s version of Canapé is also offering treats for both eye and ear in the form of a room installation and DJ sets. Based on this recipe, the team centered around Zarina Friedli has managed to create a minor sensation in the local gastronomic scene—all the while doing her part to make the good old open-faced sandwich acceptable once again in “polite circles.”

Text: Samara Leite Walt

Photos: Jana Jenarin Beyerlein

Artist and Librarian

LIONNE SALUZ

The library of the Basler Kunstverein is housed in a location that is both central and hidden: a building to the rear of Kunsthalle Basel. To get to Klostergasse 5, beyond the Tinguely Fountain, one must either cross Theaterplatz or, if approaching from Steinenberg, head straight for the entrance of Stadtkino Basel, where there is a small, discreet doorbell. Many people come here to find out more about contemporary art. The public library’s main clientele comprises artists, curators, art historians, designers, and art aficionados who seek inspiration here. The library, with its holdings of around 30,000 books, including numerous first editions and art magazines, is a veritable place of pilgrimage for anyone who appreciates art. Its facilities include an extraordinary reading room that makes its users feel as though they were above the roofs of the city.

“The emphasis of the library is on contemporary art and art education. It was originally a library for artists and art lovers” explains Lionne Saluz, who has headed the library since 2022. Herself an artist, Saluz talks about the library’s roughly 200-year history. Its origins and development are closely linked to the history of the Basler Künstlergesellschaft, established in 1812, and the somewhat younger Basler Kunstverein. And this has an impact on the library’s program. “Kunsthalle Basel has always been one step ahead of time,” says Saluz. “And so is the library.” Saluz was born in Lucerne in 1990 and graduated from Zurich University of the Arts (ZHdK) in 2017. Before studying art, she trained as a bookseller. From 2013 to 2021, she was cofounder and codirector of the M35 off space in Lucerne.

We walk through the library’s rooms, which occupy three floors. The alphabet of artists here runs the gamut from A (Marina Abramović) to Z (Alexander Zschokke). One shelf contains new acquisitions, presented with covers facing outward, among them books by Sandra Mujinga, Ida Ekblad, Sarah Margnetti, and Hannah Weinberger. On one of the rear shelves, rarities by Dieter Roth lie concealed in gray archival boxes.

“Open access to the books is one of the advantages of the library,” Saluz explains. “This is a library to be ‘present’ in.”

As the books are arranged directly side by side, contexts and relationships become apparent. This also means that it is easy to come across books one didn’t even know one was looking for.

Sometimes the library becomes a piece of art in its own right. In 1985, it was the scene of a meeting between Joseph Beuys, Jannis Kounellis, Anselm Kiefer, and Enzo Cucchi for a multi day marathon discussion instigated by the library’s then-director, Jean-Christophe Ammann. The discussions ultimately gave rise to a book. And in 1999, Cologne artist Candida Höfer photographed the empty library outside of opening hours and incorporated it into her Leseräume image series. This resulted in an elegant conceptual loop: the book containing photographs of the library itself became part of the library that had been photographed.

Text: Kito Nedo

Photos: Jana Jenarin Beyerlein

Sticker-Artist

NIEMER

Anyone traveling by train to Basel’s main station from anywhere in the urban area or from other parts of Switzerland can still see it: the celebrated “Line,” as it was dubbed in the 1990s. Badly faded over the years, the spectacular graffiti paintings, throw-ups, and tags are like relics from a time in which hip-hop was still all about protest and counterculture. “Y bin e Schprayer, und y schpray’ won y will” (I’m a sprayer and I’ll spray where I want)—back in 1991, these were the lyrics at the start of “Murder by Dialect” by Basel’s Black Tiger—the very first rap song in Swiss German.

It was this attitude that would later give rise to the street art scene. Thanks to the viral nature of the internet, projects by artists like Banksy, Obey, and Space Invader were transformed overnight into worldwide cultural phenomena. Pop made a comeback in the new medium. With the addition of a touch of social criticism, the stencil became as important to artists such as Banksy as the silkscreen was for Andy Warhol. And thus the street-art mainstream was born, a style of art that was loved by many—with exhibitions in galleries and guided tours organized to view it—and hated by others due to its banality and facile messaging.

“Street art is gentrified graffiti for people who work in offices, just like I do,” jokes Niemer, one of Basel’s sticker pioneers. Almost ten years ago, he gave the city the “Niemert wöt das” sticker, which translates to something like: “No one wants that.” Suddenly it was everywhere; a form of casual protest, this simple gesture of charming dialect was used to cancel advertising and political campaigns, construction sites, or illegally parked cars in a manner reminiscent of the so-called destroylines used to cross out other works of graffiti.

“I’m a child of the internet who

grew up with memes”

Niemer says. He defines his own art as a digital “shitposting” corner rather than a product of the graffiti or street-art tradition. Inspired by the black-and-white palm-sized sticker in Impact font, a veritable wave of stickers has now overtaken Basel with even soccer ultras or public and private institutions getting in on the action. Together with the Slap Me Baby collective, Niemer organizes a sticker convention each year for anyone interested in doing the same. They have also put out five issues of a zine, which appears in a familiar internet aesthetic and contains specifics about sticker highlights, essays, and interviews. Every year, in addition to workshops, convention attendees will find an “all-you-can-eat self-service sticker buffet” where they can take and leave behind as many stickers as they want. And there are plenty who do just that. Logo hacks such as dini muetter (Demeter), fan statements like Über Allem Kläbsch Du, anti-fascist stickers, and elaborate hand-painted messages are now encountered everywhere from street signs to toilet stalls. They help shape the identity of the city’s public spaces.

Text: Claudio Vogt

Photos: Pati Grabowicz

Artist

KASPAR MÜLLER

Kaspar Müller suggested Berlin’s Gemäldegalerie as a venue for our meeting. Not a lot is happening in this museum of thirteenth- to eighteenth-century European art on a Wednesday morning in mid-April. A couple of retirees, a kindergarten group, and a class of elementary school pupils are making their way through the rooms. The very old and the very young. They spread themselves out among the rooms, in front of the paintings and on the benches in between, almost as if they were the subjects in one of Thomas Struth’s Museum Photographs.

Müller, who was born in 1983, says he often comes here to see the collection “because you know what you’re going to find.” For example, Lucas Cranach the Elder’s The Fountain of Youth, which he thinks is “hilarious,” or—another one of Müller’s favorites—Christ with Saint John and Angels from the workshop of Peter Paul Rubens, in which we see two well-fed cherubs, an infant Jesus, and a tiny John cuddling together amid an assortment of ripe fruit. He likes to look at all of the figures that have been painted over the centuries, all the different ways of representing things, be they religious, political, or historical in nature. In search of connections between the art hanging in the Gemäldegalerie and Müller’s own art you could draw a connection between these representational models. But he does not translate these models into figurative oil paintings. Müller’s modes of expression are different. His work includes sculpture, installations, painting, drawing, photography, and video.

For Art Basel’s Parcours, he will adorn the city’s Münsterplatz with a sculptural group made of straw.

This is something that will be familiar to anyone acquainted with the artist’s work. He showed similar straw figures with forms resembling human bodies at the Kunsthaus Baselland in 2009, and similar sculptures appeared again in the form of his Five Figures in an exhibition of the same name at Berlin’s Société gallery. Repetition is a key aspect of Müller’s artistic practice. He has repeatedly created large numbers of similar works or reprised existing series in varying contexts and different locations.

The artist has been splitting his time between Berlin and Zurich since 2011, and started teaching at the École cantonale d’art (ECAL) in Lausanne in 2015. Upon finishing high school, Müller moved from Schaffhausen to Basel, where he worked in a bank for a year before studying art at the Basel Academy of Art and Design FHNW. After earning his degree, he began studying sociology and philosophy at the University of Basel—a course of study that he never completed. What remained with him, however, was an interest in the forms and processes of living together, while in the realm of philosophy he is particularly drawn to speculative realism. He opened two project venues in Basel: Vrits (2006–9) and, later, Galen (2009–10). “The early years are defining for an artist,” he says. He cherishes Basel; for a city its size, the art scene is of an extremely high quality. He also likes the city’s independent, eccentric flair, the seriousness with which it approaches its carnival, for example, where “everyone eats gruel together at 4 am,” and “even the boss of UBS comes along.”

His curious straw figures fit in well there. For Parcours, he transferred them outdoors for the first time. Six of the figures will be grouped in a loose constellation on Münsterplatz. Significantly larger than previous variants, the figures are more abstract, with new postures and authoritarian gestures reinforcing the sense of exaggeration created by their proportions and the similarity between the sculptures and the audience. As Müller says, “It’s difficult to ignore something with arms and legs.” And just like the proverbial straw man, the sculptures appear as a kind of placeholder or substitute.

But for what? As is often the case with Müller’s works, the materials they are composed of—wood, metal, string, linen, and, most importantly, straw, “completely natural and disposable”—are offering a number of interpretative approaches. With traditions deeply rooted in Swiss agriculture, straw is closely connected with centuries of cultural history in Swiss homes, farms, and handicrafts. Another factor that comes to mind is the manner in which the history of the material has been adopted and developed in Western consumer societies, where bales of straw are sold as decorations meant to communicate a sense of earthiness and coziness.

Müller’s art often focuses on these types of values and their anchorings. For instance, what happens when examples of a particular object are lined up one after another to the point where they begin to look generic? It’s a phenomenon the artist has examined using colorful, handblown glass orbs or countless photographs of Lake Zurich taken over a period of more than a year. The artist’s ultimate interest is in how the concurrence of analog and digital enable the two forms to influence one another, and how this controls our perception. His glass orbs look as if they could have been created on a 3D printer, and his straw figures are reminiscent of rendered objects. The fact that they are anything but can only be confirmed at the analog level. Be sure to pay them a visit on Münsterplatz during Art Basel.

Text: Beate Scheder

Photos: Mark Peckmezian

Multidisciplinary Artists

OKRA COLLECTIVE

Whether at the Gessnerallee theater, the Gurtenfestival, or in Barcelona, the members of the Okra Collective have ventured well beyond the boundaries of their canton and even of Switzerland. Community building via music is the name of the game for this nine-person collective. The project is based on the idea of appropriating spaces that had previously been denied to them, crossing visible and invisible gulfs, and building bridges to artists in other parts of Switzerland. All of them have experience as DJs, performers, producers, and event designers, yet they regarded it as essential to organize themselves as a collective.

It all began in 2020, the first summer of the COVID-19 pandemic. Equipped only with CDJs and mini speakers, they organized joint kitchen parties in the apartment in St. Johann where Okra member Katie Omole used to live. “It was a special time, and we were dying for a chance to exchange ideas with others and to stage a kind of gathering. Black Lives Matter then put the wind in our sails.

We wanted to stop just being observers in the local cultural landscape and instead get actively involved in the music scene,” Mirco Joao-Pedro, DJ and art director of the group, recalls.

So that’s exactly what they did; less six months year after their founding, Okra presented themselves to the public with a mini festival on the premises of the Hirscheneck restaurant. From the graphics to booking and set design, they did everything themselves. The music events were soon supplemented by interdisciplinary formats embracing the genres of performance and art. At last yearʼs Art Basel, for example, some members of the collective organized a kind of guerrilla art exhibition entitled they dared to dream, featuring exclusively works by artists from their “family,” as they call it. Symbolically, the exhibition took place in the very center of Basel at the notorious intersection between Feldbergstrasse and Klybeckstrasse. This is a location where the cultural precariat meets gentrification, where coworking spaces exist alongside designer boutiques, kebab shops, and local grocery stores.

At this year’s Art Basel, Okra is staging a party in the trendy club Rouine in the Kleinbasel district. While they’re returning to their artistic roots, they do not exclude future collabs outside the music sector: “We would like to do more of those types of interdisciplinary collaboration”, Joao-Pedro adds.

Text: Samara Leite Walt

Photos: Jana Jenarin Beyerlein

Biologist

MARKUS RITTER

The first thing you notice in Markus Ritter’s house are the books. Even the staircase houses a well-stocked shelf containing classics of critical theory: writings by Theodor W. Adorno, Hannah Arendt, Walter Benjamin, Jürgen Habermas, Max Horkheimer, and Herbert Marcuse. The library continues in Ritter’s workspace. At its core is an epistemological treasury: one whole wall full of science titles, some of them as rare vintage editions. There is, for example, Erwin Stresemann’s four-volume Exkursionsfauna. Published in East Berlin in the mid-1970s, the noted ornithologist’s standard reference for identifying insects, invertebrates, and vertebrates is known in biology circles simply as “Stresemann.” No less imposing is the three-volume treatise Die Alpen im Eiszeitalter by geographers Albrecht Penck and Eduard Brückner, which was published by Christian Bernhard Tauchnitz in Leipzig in 1909. “Penck and Brückner is the standard historical reference for alpine glaciology,” Ritter explains, “the first comprehensive description of the process of glacier formation in every alpine valley.” It’s a strange feeling to hold a book about alpine glaciers in your hands that’s over a hundred years old while discussing the melting of the glaciers as a symptom of today’s climate crisis.

Markus Ritter, who was born in Basel in 1954, studied biology and botany.

“I’m fascinated by nature,” he says. “Even as a child I was already

collecting snails.”

In 1968, during his teenage years, he became aware of the need for environmental protection. His first permanent job, in the mid-1970s, was with the Swiss Ornithological Institute in Sempach. In the early 1980s, he returned to Basel to work for the Swiss horticultural exhibition Grün 80, which was held on the site of what is now the Merian Gardens. Shortly afterward, Ritter was one of the authors of the Basler Natur-Atlas, published in the mid-1980s by Basler Naturschutz. This was the first register of urban spaces that merited protection and were classified as ecologically valuable. The three-volume urban inventory, which also covers mosses, lichens, beetles, butterflies, spiders, small mammals, and birds, sought to offer recommendations and was meant to serve as a basis for politicians and authorities to make decisions about the provision of more natural spaces in the city.

The year 1986 was marked by the Chernobyl nuclear disaster and the largest chemical accident in Swiss history. In November of that year, 1,350 tons of chemicals caught fire on the premises of the Sandoz chemical group in Basel. The chemicals and the contaminated quench water poisoned the Rhine along a 250 km stretch and caused the mass death of fish. Ritter went into politics the same year. Together with sociologist Lucius Burckhardt and his wife, object artist Annemarie Burckhardt, he founded the green party Grüne Alternative Basel (GAB) in 1986. The party merged with the Grüne Partei Basel Stadt (GPBS) in 1989. Ritter was a member of the cantonal parliament from 1988 to 2001 and in 2000 became the first Green to serve as speaker of the parliament. Between 2006 and 2018, he worked as secretary of the presidential department Basel-Stadt. Since his retirement from active politics, he has stepped up his work as an author, expert, and editor in the fields of environmental and conservation history, ornithology, botany, and landscape theory. Occasionally, he hosts a “spiritual-ecological city walk” through Basel. Ritter enjoys sharing his comprehensive knowledge, and his eyes light up when he talks. Listening to him is a pleasure.

Since 2012, Ritter has been working on the estate of Lucius and Annemarie Burckhardt, most of which is held by the Basel University Library. Today, Burckhardt is regarded as a pioneering figure waiting to be rediscovered by each new generation of practitioners in art, architecture, and landscape theory. Burckhardt kick-started many things, such as the discipline of strollology or promenadology as well as urban planning criticism and the discourse on sustainability. “It’s becoming more and more obvious how far Burckhardt was ahead of his time, and how we’re only just beginning to understand him,” says Ritter. Burckhardt’s Anthologie Landschaft, edited by Thomas Kissling, is due to be released by Lars Müller Publishers in Zurich. “The book is the fruit of his lifelong study of landscapes,” says Ritter, who discovered the substantial manuscript about ten years ago among Burckhardt’s papers.

After curator Hans Ulrich Obrist’s Lucius Burckhardt and Cedric Price: A Stroll through a Fun Palace—which featured in the Swiss Pavilion at the 2014 Venice Architecture Biennale—drew international attention to Burckhardt’s ideas and oeuvre, the next major event is now on the horizon. Numerous events and exhibitions are being planned in Switzerland and abroad to mark what would have been Burckhardt’s hundredth birthday in 2025. A nonprofit association is being founded to support these varied activities.

Text: Kito Nedo

Photos: Jana Jenarin Beyerlein

Sustainability Manager

CARLOTTA THOMAS

Carlotta Thomas works as sustainability manager at Liste Art Fair Basel. Born in Bonn in 1993, she studied communication design and European media studies in Potsdam. She has lived and worked in Basel since late 2021—which means it’s high time we got together for a chat.

Kito Nedo: The first edition of Liste as a new fair for the young generation of artists and gallerists took place in 1996. What is the role of sustainability in the context of today’s art fairs?

Carlotta: Thomas: Sustainability has several aspects: the ecological, the economic, and the social. In the Liste team, we began by discussing these aspects to develop a basis for further action. Then we set ourselves internal and external goals. It’s important to us to have spaces at the fair for engaging with the issue. For this year’s edition of Liste, we are planning an emphasis on “resilience,” and our curator, Sarah Johanna Theurer, has invited various artists to reflect on this theme.

KN: What does one have to do to make an art fair more sustainable?

CT: For one thing, you can reuse materials such as building and packaging materials or signage. This year, we’ll be setting up water stations at the fair for the first time, so everyone will be able to fill their own water bottles.

But sustainability can also mean disseminating information about sustainable actions.

We’ve started compiling and publishing information for participating galleries and visitors to help them choose more climate-friendly options.

KN: How do you verify a fair’s sustainability?

CT: The main thing is transparency. We’re an active member of the Gallery Climate Coalition (GCC), which was formed in 2019. This is an important community. It established a forum, and the whole thing continues to develop through discussions and the exchange of ideas within the art sector. For the last two editions of Liste, we compiled a CO2 report. It’s important to write these reports to identify and document the measures. It gives us a way to track and verify the efficacy of individual measures going forward.

KN: What can visitors do to contribute to a fair’s sustainability?

CT: The main thing is climate-friendly travel. It’s best to take the train. Deutsche Bahn offers an event ticket that can get visitors from Germany to Basel at a reduced rate. For those arriving by air, it makes a big difference if they fly economy class and take direct flights. International actors will continue to travel and continue to fly. But I can see a growing awareness of the need for us to ensure that our planet remains a livable place and to change behaviors that are harmful to the climate. This is part of where our responsibility as an art fair lies.

Text: Kito Nedo

Photos: Jana Jenarin Beyerlein

Architects

TRUWANT RODET

“We want to transcend frontiers,” emphazise the architecture duo of Charlotte Truwant and Dries Rodet. Since 2010, Basel has offered optimum conditions and resources for the architecture team of Truwant—who hails from the French alps—and her Belgian partner, Rodet, who together founded the studio of Truwant + Rodet +. This hub in the tri-national area has always been a fertile meeting point. Borders between territories, between city and landscape, between nature and culture dissolve here and become permeable. This fosters Truwant and Rodet’s approach, whose definition of architecture is broad and fluid and explicitly includes, for example, researching Basel’s relationship with the Rhine and water in general. During the city’s first architecture week, Architekturwoche Basel 2022, their project Cyclical Tales—Zyklische Erzählungen traced the rivers and waterways in Basel, from bathing in fountains, Brunnen Gehn, to enhancing a very high fountain at the Rhine promenade, Rheinfontäne, as interventions in urban space.

The two architects met in Copenhagen in 2007. After studying architecture in Lyon, Truwant had completed her master’s in architecture at EPFL in Lausanne. Rodet, who studied and graduated in Ghent, was working for an architecture firm. When they finally founded Truwant + Rodet + in Basel in 2017, they had already gained copious international experiences in the practice and teaching of architecture in Rotterdam, Brussels, Japan, Zurich, Lausanne, and Paris.

They regard architecture as a process. The historicity and cultural progressiveness of Basel offers the duo a dense context and deep layers in which to dig and anchor their themes. Basel is a city that thinks outside the box. The architecture duo’s projects transcend disciplines and scales—as the plus signs in their names suggest. “Time as Material” and “Uncertain Conditions”—their tools are proximity and relationships. The “+” indicates their readiness to undertake interdisciplinary work in which places, themes, and collaborative practices stimulate one another. Together with a small team, the Franco-Belgian studio is part of the Garage, an interdisciplinary office community in a former car repair shop situated near the University of Basel. Since 2018, both have been co-operators of dasVerein, a nonprofit platform that initiates lectures and workshops outside the institutional sphere. Together with the French architecture office ASBR, Truwant + Rodet + are currently renovating the Centre culturel suisse in Paris. During Art Basel, the practice is responsible for the scenography of the Swiss Art & Design Awards in Messehalle 1.1. For over a week, this will become a meeting place spanning 8,000 sqm dedicated to the celebration of the moment.

Text: Chrissie Muhr

Photos: Jana Jenarin Beyerlein

Landscaper

CAROLA ZIEREISEN

At what time of year does Piet Oudolf’s garden in Weil am Rhein, with its perennials, grasses, shrubs, look its best? The famous Dutch landscaper and garden designer says that his favorite months are September and October, when the beauty of decay spotlights the transience of everything in nature. For him, it’s important “not to pull out everything as soon as it stops flowering and to let things that don’t conform to conventional standards of beauty have a place. Brown is a color too.” In the eternal spectacle of growth and decay that unfolds on the Vitra Campus with spectacular unobtrusiveness ever since the garden was laid out and planted in May 2020, the fall is just another moment in the life of a “community” of carefully selected plants with different flowering times and life cycles; it is the sum of its individual parts.

Landscaper Carola Ziereisen has been head gardener in charge of the garden since its inception. She works for the company Jürgen Eise Garten- und Landschaftsbau, based in Weil am Rhein. In May 2020, up to eight workers spent eleven days laying out and planting around 36,000 perennials. “That was a logistical challenge,” Ziereisen says of the landscaping feat. “We had his plan, and we somehow had to transfer it onto the site.” The landscape architecture comprising 4,000 sqm on the Vitra Campus, itself replete with architectural sights, now attracts horticulture enthusiasts from all over the world. Last year, for example, a travel group from South Korea came all the way to Weil just to see the garden.

We strolled with Ziereisen along the winding paths of pale granite chips. “The idea is for you to be able to lose yourself in these gardens.” Its nonlinearity is deliberate, she explains. Little hillocks add to the charm of the layout. These level differences are created on purpose. Everything is beautiful here, but not mellow. He was really only trying “to make people’s fantasies real,” says Oudolf. And this reality takes some maintenance. Ziereisen comes by once a week to check on the plants. She doesn’t use the word “weeds,” preferring to call them “wild herbs” or “extraneous growth.” When she discovers a gap, she replants it with a perennial or divides a plant. Occasionally, she takes a picture to post on her Instagram account @crazy.gardener, which offers a time-lapse view of how the Perennial Garden was established and how it continues to develop. Sometimes, Oudolf sends her a message about the garden. He follows her account.

Text: Kito Nedo

Photos: Pati Grabowicz

Artist and Activists

DORIAN SARI & FRIDAYS FOR FUTURE

In Basel’s history, a few groundbreaking steps were needed before the “city of museums” gained its worldwide reputation. Thanks to the foresight of intrepid Baslers, today Kunstmuseum Basel, the world’s first public art collection, and Kunsthalle Basel, probably the oldest institution for contemporary art, are situated in close proximity to one other. In November 2022, the people of Basel voted to make the city carbon-neutral by 2037. This made Basel the first canton to mandate its government to enshrine a climate target in law and bind it to a specific date, on the basis of the long-term climate strategy adopted by the Federal Council for 2050.

The climate justice initiative inspired Dorian Sari to think more deeply about the connection between art and the climate crisis. Since the referendum, the artist has invited three Fridays for Future (FFF) activists—Anatol Bosshard, Helma Pöppel, and Benjamin Rytz—to exchange ideas with him every week in his studio.

Can art institutions become role models in fighting the climate crisis? The group thinks they can. After all, a lot of other shifts have taken place recently. Much has changed in the art scene in terms of equal opportunities, accessibility, critical whiteness, and decolonization: there have been exhibitions and panel discussions on these issues, language has become more inclusive, and institutional structures have been critically examined. The task now is to bring climate more directly into the discourse.

Alongside specific targets and demands, the four-person group is also interested in mediating in an increasingly polarized debate. “We want to meet in the middle of the bridge,” says Sari. The sense of alienation between activists and people in power is alarming. The media also bears responsibility for fueling public discontent by focusing on radicalization. “Activism is a spectrum,” Bosshard adds. Civil disobedience is also a part of democracy.

But the FFF activist and his colleagues are not interested in smearing mashed potatoes, cakes, and tomato sauce on artworks.

What interests them is dialogue: giving people hope and shaking them out of their paralysis. “Climate action is not about banning things. It’s about finding a better way to live,” Bosshard stresses. “We want to engage in dialogue,” adds Sari, who organized a round table on the issue at Kunsthalle Basel in May. The group developed a plan of action and presented a roster of ideas. Let’s hope the participants are ready to break new ground. After all, they owe it both to the history of their institutions and to the future of the people of Basel.

Text: Claudio Vogt

Photos: Pati Grabowicz

Designer

ELEONORE PEDUZZI RIVA

Eleonore Peduzzi Riva’s business card identifies her as an architect. Since the 1950s, she has headed a successful firm with expertise in engineering and has worked as a consultant for many Italian companies. Peduzzi Riva says that her work always involved great “moral” responsibility. She worked for Italian furniture company De Padova for almost fifty years, selecting designers, creating exhibitions, and supervising production. In the old De Padova catalogs, it is hard to find a photograph that fails to show Peduzzi Riva next to entrepreneur Maddalena de Padova, who founded the company.

In the fast-paced, production-centered Milan of the 1960s, she designed several products under her own name: a spiraling ashtray, a lightweight chair, a glass table lamp, an “endless” sofa. She created the famous DS-600 sofa for the Swiss company de Sede together with the three Swiss designers Ueli Berger, Heinz Ulrich, and Klaus Vogt. The collaboration was her own idea, because she was bored at the prospect of designing yet another sofa by herself. As she always had a continual stream of queries and worked all through the day, she cultivated the habit of not smoking until 6 pm. She has kept up this habit to this day.

“I don’t think about what I want to do in the abstract, it just comes to me.”

Peduzzi Riva is conscientious, fast, cheerful, and modest. Her face is dominated by round white spectacles. Their shape and color go back to one of her designs that is still sold by an optician near Milan Cathedral. She has worn large glasses since her youth, always with round white frames. She is from Basel, although for a long time people thought she was Italian. She only returned to Switzerland after falling in love for the third time. “I worked in Milan. In Riehen or Basel, I didn’t do anything for my career.” She knew and worked with all the important people in Milan. She would meet them in the Jamaica bar in Brera, then the most popular meeting place in the city. “All the friends I developed with professionally are gone now: Achille Castiglioni, Cini Boeri, Gae Aulenti, Ettore Sottsass.” She turns down any requests she receives from journalists who want to portray her as a “dinosaur from a past generation.” Out of false modesty—but also because she can’t be bothered. She says with a laugh: “I understand this motivation, but they want to sell me as the last survivor of a long-extinct species. I don’t find that very funny.” This year, Peduzzi Riva will be awarded a Grand Prix of Design by the Swiss Federal Office of Culture. The annual prize, which brings recognition in the form of publicity and money, is awarded parallel to Art Basel. Peduzzi Riva is sanguine about it: “I didn’t even know this ‘Grand Prix’ exists, because I always go to Art Basel.”

Text: Tinka von Schrei

Photos: Pati Grabowicz

Artist Collective and Project Space

PALAZZINA

When PALAZZINA invites people round for coffee and cake, visitors might just find themselves inside a room that is dominated by an enormous art installation, while all around, the inhabitants of the apartment sit slurping from their mugs. “We’re a group of twelve artists who have been living together since 2019, and we organize exhibitions and happenings at home,” explains Noemi Pfister, one of the group’s founding members. After moving to Basel, she and Victoria Holdt, with whom she had studied in Geneva, started talking about how they wanted to live and how to combine this with their artistic practice. Both of them had plenty of experience living communally with several people. But they both needed somewhere to live and wanted a place that would be big enough and open-minded enough to allow them to put on exhibitions. Through one of their lecturers, they found an abandoned house on Schweizergasse. Pfister and Holdt were soon joined by their friends the artist duo Simone Holliger and Mathieu Dafflon as well as others. “All in all, it was quite a gamble, because we didn’t know everyone, and we didn’t even know ourselves whether the idea of living together and running an off space was really feasible, and whether everyone would support it,” Holdt recalls.

But the gamble paid off, and in July 2019 they held their first show with works by Sofia Durrieu and Rebecca Kunz. “When choosing the artists, it was important to us from the start that we had a good mix of people, with some who were just starting out and others who were further along their career path,” Holdt explains. Much has happened since the early days in the first PALAZZINA location. Two moves and nineteen exhibitions later (featuring the likes of Maya Hottarek, Val Mining, Alex Ghandour, and Paulo Wirz), PALAZZINA has found a new home in Allschwil.